To assist municipalities in implementing the Agriculture & Farmland Protection Plan recommendations, and to provide a place to find best practices in local regulation and planning support for agriculture, the project team has created this Farm-Friendly Toolbox. The Toolbox is intended to help municipalities integrate and update their land use plans and regulations as they relate to supporting agricultural land uses, address new and changing dynamics in agriculture, and ensure consistency with NYS Agriculture & Markets laws.

Download the full Farm-Friendly Municipal Toolbox PDF here.

In New York State, land use is controlled primarily at a local level, and thus, municipalities have a critical role in effective protection of agricultural lands. Meanwhile, agriculture has evolved in multiple ways over the past several decades and will continue to evolve into the future. Throughout, it has remained a very diverse and robust economic sector in Onondaga County. Through partnerships with local farmers, municipal governments can work to plan for the long-term viability of their agricultural sectors and create local land use regulations that are up to date, farm-friendly, and meet the needs of the community as well.

There are several tools available to assist communities that desire to protect the agricultural land resources and enhance the long-term viability of agriculture. This Farm Friendly Toolbox provides an overview of these tools and is designed to assist local governments in navigating through the many recent changes to agriculture, as well as agricultural policies within NY, such as the protections afforded agricultural operations through the Agriculture and Markets Law. Local governments can use this toolbox

- In reviewing zoning and other land use regulations to ensure they are up to date as they apply to agriculture

- As a resource to consult when creating or updating the community’s comprehensive plan, or a farmland protection plan, or other local planning efforts

- As a resource to consult when creating or updating the community’s zoning, subdivision, and other land use regulations

In reviewing proposed new development for consistency with the community’s goals.

Historically agriculture has included a variety of disciplines aside from fruit, vegetable and crop production and livestock raised for food. For the purposes of this document, agriculture is the use of land, buildings, structures, equipment, manure processing and handling facilities, and practices which contribute to the production, preparation and marketing of crops, livestock and livestock products as a commercial enterprise or a hobby and including commercial horse boarding operations as defined in New York State Agriculture and Markets Law (AML) Article 25-AA, Section 301. Activities such as animal husbandry, or the breeding of specific animals for use or sale (e.g., racehorses), beekeeping, aquaculture (fish production), horticulture, floriculture and silviculture are all considered agricultural pursuits as well. One of the most notable changes in agriculture has come under language “preparation and marketing of…products as a commercial enterprise or hobby” added under AML Section 301. Direct farm marketing has also expanded beyond the temporary, seasonal farmstand selling produce grown on the farm to include numerous processed products, from meats to cheeses to baked goods, to wine, beer, cider, and spirits, not only in person but via the internet as well.

Within this context, the Farm Friendly Toolbox is intended to help local government and the farm community address agricultural issues within Onondaga County through planning, zoning, preservation programs, and other land use regulations.

Overview

Local planning initiatives are a key component in promoting the health and long-term viability of the community’s agricultural sector. It is critical that local planning in agricultural communities thoroughly address the challenges, as well as the opportunities, weaknesses, and strengths faced by the agricultural sector. Integrating agriculture into the long-term vision for the community, as well as into planning goals and strategies, facilitates the careful balance of agricultural land protection and facilitates the flexibility needed by contemporary agricultural operations to grow and develop.

Beyond traditional agricultural plans, agricultural viability and farmland protection can dovetail into several types of planning efforts, including comprehensive planning, open space planning, and economic development planning. The purpose of this section of the Farm Friendly Toolbox is to assist municipal officials to identify potential issues and opportunities in their local planning tools as they relate to agriculture and to find areas, if any, where plans could be amended to build a more farm friendly community.

Comprehensive Plan

The comprehensive plan sets the long-range planning goals and objectives for the community and can have an important impact on agriculture in the community through proposed policies and actions, including regulations and capital investments. It can outline actions to protect the agricultural land resource, such as identifying areas to be protected for agriculture and areas where growth will be encouraged, outline actions to promote the long-term economic viability of local agriculture and outline local farmland protection strategies to be implemented. Key elements of a farm-friendly comprehensive plan include:

- An inventory of existing agricultural operations in the community and their characteristics

- Identification of the challenges, opportunities facing local agriculture, and the strengths and weaknesses within the agricultural sector

- Identification and mapping of high-quality agricultural lands (prime soils and farmland of statewide importance) within the community

- Recognition of the importance of agricultural land as a natural resource and move beyond viewing farmland “simply as land in reserve for future urban development” (American Planning Association. 1999. Policy Guide on Agricultural Land Preservation)

- A clear set of goals, objectives, and policies to protect the agricultural land resource, and promote the long-term viability of local agriculture

- Land use and infrastructure development plan recommendations that call for channeling future development aware from agricultural areas within the community

Agriculture & Farmland Protection Plan

Agriculture and farmland protection plans (AFPP) can be an important supplement to the comprehensive plan. They can be and stand-alone plan or integrated into a comprehensive plan. Standalone AFPPs are often funded by NYS Department of Agriculture and Markets. The benefit of an AFPP is that it brings farmers, local officials, and non-farmers together to focus directly on the issues facing agriculture in the community and develop policies and actions. A critical element in any AFPP is the involvement of the farm community in setting a vision for the future of agriculture in the community and creating goals and objectives designed to further that vision.

Adopted agriculture and farmland protection plans completed to the specifications of the Department of Agriculture and Markets position local governments to participate in state-funded purchase of development rights and other programs. Key elements of an AFPP are an analysis of the local conditions, including lands in agriculture, lands owned and rented by farmers, location and extent of prime agricultural soils, parcels in agricultural districts and farmers participating in agricultural district programs. In addition, the plan should include a review of zoning and subdivision regulations, as well as existing and planned sewer and water infrastructure and their implications for agriculture.

The agriculture and farmland protection plan should also include specific recommendations for policies and actions to be implemented by the local government to promote the long-term viability of its farm sector. Implementing specific elements of a plan often requires a collaborative effort between the local government and farmers, as well as local government, county and state agencies, Soil and Water Conservation Service offices and Cornell Cooperative Extension, and so it is important to identify which agencies will take the lead on implementing the various recommendations, as well as secure potential funding sources. In addition, the plan should identify those agricultural lands or areas that are proposed to be protected through zoning, easements, or other options.

Open Space Plans

The open space plan sets the long-range planning goals and objectives for the community that focus on the identification and protection of key open space assets. Generally defined, open space is land that is not intensively developed for residential, commercial, industrial, or other land uses. Open space can serve many purposes in the community, as park and recreational space, undeveloped publicly or privately owned scenic lands, agricultural and forest lands, as well as lakes and ponds and their shorelines, and wetlands. Agricultural lands in the rural areas of Onondaga County make up the largest component of open space, and hence their protection contributes to the overall character of the community.

An open space plan can recommend a wide variety of steps relevant to agricultural uses that a community can take such as: 1) creating zoning regulations of key open space areas that channel intensive development away from such areas, including agricultural areas; 2) identifying lands, including agricultural lands, that warrant permanent protection through purchase or donation of development rights; and 3) identifying important scenic views and viewsheds and incentivize their protection.

Economic Development Plans

According to the Central New York Regional Planning and Development Board, agriculture in New York contributes some $15.5 billion annually to the State’s economy. Although viewed primarily as a land use, agriculture is a key part of the economic base of many communities that provides both direct employment and raw materials for food processing industries throughout the state.

Local economic development plans that integrate agriculture as one element in a diverse economic base can identify challenges and opportunities for farmers, and policies and actions that can benefit the agricultural sector. These actions can include initiatives that support agriculture such as food hubs, new industrial development to provide markets for regional agriculture, and grant programs for capital investments in areas such as on-farm biofuel production from manure.

Overview

For the purpose of this toolbox, regulatory tools are the various instruments through which local governments manage growth and development within their boundaries. They guide local officials as well as residents, businesses, farmers, and others in day-to-day decisions. Well-crafted regulatory tools protect the health and welfare of the community and provide for efficient allocation of land and other municipal resources while providing the flexibility needed to prosper economically in an evolving global economy. They are also constantly evolving as new opportunities, and new issues arise.

In many New York municipalities, local land use regulations were written in a time of contraction of the agricultural sector and rapid population growth which fed visions of ever-expanding suburbs coupled with views of agriculture as a “transitory land use.” After decades of this trend, however, even in relatively urbanized Onondaga County, 16 of its 19 towns still have land in active agriculture.

Additionally, zoning regulations affecting agricultural operations have not always kept pace with trends in agriculture and agricultural practices. This has often resulted in outdated regulations being applied to agricultural operations, resulting in unintentional but potentially unreasonable restrictions for farmers. Examples include direct farm marketing, on-farm wineries, breweries, cideries, distilleries, agri-tourism, bed-and-breakfast inns and other supplemental farm businesses. These agriculture-related enterprises, when operated as an accessory use to an ongoing agricultural operation, can provide revenue streams that enhance the economic viability of the farm operation. They can also provide valued goods and service to residents, strengthen the local food production system, and contribute to the overall local economy through tourism development.

The purpose of this section of the Farm Friendly Toolbox is to assist municipal officials to review their local land use regulations and to find areas, if any, where regulations could be amended to create a more farm friendly regulations.

Right to Farm Laws

New York State adopted its initial right-to-farm law in 1982, and since then numerous counties and town have adopted similar laws. These laws are intended to protect those within it from nuisance lawsuits over matters like noise, odors or dust associated with agricultural operations. The State law protects farms located within county agricultural districts; however towns and villages can adopt right-to-farm laws that would apply to all farms within their boundaries. While viewed primarily as designed to protect farmers from so-called nuisance suits, local right to farm laws can be useful in other ways. In suburban municipalities where agriculture and development often occur side-by-side, a right to farm law can be a tool for raising public awareness of local agriculture.

Many towns have also utilized local right-to-farm laws to set up a framework for conflict resolution and to for enhancing communication between the farm and non-farm communities in the town. Although many farms in Onondaga County participate in the County-administered Agricultural Districts program and are afforded protection under the NY Agriculture and Markets Law, not all farms are located within an agricultural district. A local right to farm law can apply these protections to all farms located in the community.

Local right-to-farm laws vary considerably in scope and length. The core language found in a number of local laws however is:

Farmers, as well as those employed, retained, or otherwise authorized to act on behalf of farmers, may lawfully engage in agricultural practices within (municipality name) at all such times and all such locations as are reasonably necessary to conduct the business of agriculture. For any agricultural practice, in determining the reasonableness of the time, place, and methodology of such practice, due weight and consideration shall be given to both traditional customs and procedures in the farming industry as well as to advances resulting from increased knowledge and improved technologies.

Town of Malta NY Right to Farm Law

Agricultural Districts

Since its adoption in 1971 Article 25-AA of the Agriculture & Markets Law has served to protect and promote the availability of land for farming purposes and provided farmers protection from adverse local government policies toward agricultural operations. The primary mechanism for this is the county-administered Agricultural Districts program that provides for the protection and enhancement of the viability of farm operations in certified agricultural districts. The benefits to farmers who participate in the agricultural district programs include:

- Limitations on the exercise of eminent domain and other public acquisitions, for specific public infrastructure projects

- Limitations on the power of local governments to impose benefit assessments or other levies for certain public infrastructure investments

- Limitations on property tax assessments levels to those that reflect the agricultural value of the land only

- A requirement that local governments avoid unreasonable restrictions in the regulation of farm operations when exercising their powers to enact and administer comprehensive plans, local laws, ordinances, and other regulations or rules and/or regulations

- A requirement that applications for certain planning and zoning actions by a local government that may impact farm operations within an agricultural district, or lands within five hundred feet of such farm operations within agricultural districts, include an agricultural data statement

The Agriculture and Markets Law Section 305-a provides farmers and agricultural operations located within County sponsored agricultural districts specific protections against local zoning regulation that may be unreasonably restrictive and cause undue interference with legitimate agricultural practices as defined by State law. The Department of Agriculture and Markets evaluation of the reasonableness of a local law regarding agriculture includes:

- Is the law or ordinance reasonable “on its face,” and whether it is reasonable when applied to a specific case?

- Is the law in question is vague to a point that it inhibits farmers from undertaking certain activities or constructing certain buildings out of concern for violating it?

- Does a local regulation unreasonably restrict or regulate a particular farmer or landowner?

- Does the farm activity in question, although a legitimate agricultural activity under the law, threaten the public health or safety?

Each case investigated by the Department of Agriculture and Markets is evaluated individually and on its own merits. If a determination is made by the Department that a local law or ordinance is unreasonably restrictive as applied to agriculture, it will communicate this to the involved municipality. The next step is for the Department to work with municipal officials to resolve the issue in a manner that protects the rights of the farmer, while also addressing the concerns of the municipality

In 2002 the New York State Legislature also amended Town Law Section 283-a to require local governments to ensure that their laws, ordinances, or other regulations that might apply to agricultural operations located in State certified agricultural districts do not “…unreasonably restrict or regulate farm operations in contravention of Article 25-AAA of the Agriculture and Markets Law, unless it can be shown that the public health or safety is threatened.”

Agricultural districts are established by local initiative, at the county level. The County legislature has the authority to create and manage agricultural districts within its boundaries. Towns however can play an important role in the program, by encouraging their farmers to participate in the program, and participating in the annual enrollment program, as well as the 8-year agricultural district renewal process.

Zoning Regulations

Overview

Local zoning and other land use regulations are the primary instruments through which local governments manage growth and development within their boundaries. They also have tremendous influence on farm operations. Local zoning has the potential to promote innovation and economic growth in the agricultural sector or restrain it. The following are the important elements of a farm-friendly local zoning code that can promote innovation and economic growth in the farm community.

An important component in any land use code, but one that is often overlooked is the glossary section that contains definitions of various terms used in the zoning regulations. Because of the nature of zoning, clarity is critical to ensuring fair and consistent interpretation of the regulations, promoting efficient administration and positive public perception, and while warding against controversy and in some cases expensive litigation. Zoning codes often have either outdated agriculturally related definitions or no definitions for many of the activities associated with agricultural operations. This section of the Toolbox focuses on agriculturally relevant elements of zoning codes, including definitions.

Purpose Statement

A short purpose statement at the beginning of the regulations for each zoning district can be very helpful in articulating the purposes and objectives of individual zoning districts and providing boards and officials with guidance as they interpret the zoning code. It can also be an educational tool for the general public, informing non-farm residents that they live in an area where agriculture is a dominant land use. In the case of zoning districts where agriculture and other land uses are mixed together, a purpose statement can communicate a “farm-friendly” message supporting agriculture as a current and long-term land use.

An example of a strong purpose statement for agriculture is:

“[The] Agricultural/Rural Zone is primarily intended to preserve farming and agricultural lands in the Town and also to maintain open space and the quality of life enjoyed by residents of the Town. Agriculture is an important part of the Town’s economy, providing both direct and indirect employment benefits, and it also provides the visual benefits of open space. This zone prioritizes and preserves viable agriculture in the Town by providing an area where agricultural operations and agricultural-based enterprises are the predominant active land uses in the zone…”

Town of Ulysses Zoning Code, Sect. 212-23

Permitted Uses

It is of course important to provide for the range of land uses that fall under the heading of “agriculture”. Historically however land use planning and zoning in many areas of Upstate New York has been premised on the perception that agriculture is a transitory land use, one that will gradually disappear in the coming decades. This has resulted in many zoning districts being designed as mixed agricultural residential zoning districts, and in more rural communities, “catch-all” zoning districts accommodating a variety of often incompatible land uses, including intensive agriculture and suburban density residential, large-scale industrial, and large-scale commercial development.

A common example of this issue is the following list of permitted uses from the zoning regulations in the Agricultural/Residential district of a rural town with high quality farmlands and a robust agricultural sector: airports, excavation and mining operations, mobile home parks, multi-family dwellings, motor vehicle service stations, hospitals, nursing homes or health related facilities, and professional office buildings. In some communities this mix of permitted uses has cause conflicts between the farm and non-farm communities. In this example, placing high density mobile home parks and multi-family dwellings, hospitals, nursing homes and health-related facilities in areas where large scale agricultural operations can be expected could have substantial adverse impacts on residents of such developments. Airports, mining operations and large-scale industrial operations can also create competition between farmers and developers for increasingly scarce agricultural land. It is important to review the permitted uses for the agricultural zoning district to ensure that the permitted uses both minimize conflicts between agricultural and non-agricultural uses and reduce competition for land resources.

Agricultural Uses

New York State recognizes a wide variety of activities (Art. 25-AAA, Section301(2)) in its definition of what constitutes an agricultural operation. These include the production and marketing of:

- field crops (grains, potatoes)

- fruits and vegetables

- horticultural specialties, such as nursery stock, ornamental shrubs, ornamental trees, and flowers

- livestock and livestock products, (cattle, sheep, hogs, goats, horses, poultry, ratites (ostriches, emus, rheas, and kiwis), farmed deer and buffalo, fur bearing animals, wool bearing animals, and milk, eggs, and furs

- maple sap

- Christmas trees from a managed Christmas tree operation

- aquaculture products, including fish, fish products, water plants and shellfish

- woody biomass from, short rotation woody crops raised for bioenergy, excluding farm woodland

- honey, beeswax, royal jelly, bee pollen, propolis, and other apiary products, including package bees, nucs and queens

- actively managed log-grown woodland mushrooms

- industrial hemp as defined in Section 505 of Agriculture and Markets Law.

Other activities that the State recognizes as agricultural operations are:

- “Commercial horse boarding operation,” or an enterprise meeting State size and income thresholds that generates income through the boarding for fee of horses or a combination of horse boarding and the production for sale of crops, livestock, and livestock products

- “Commercial equine operation,” or an enterprise meeting State size and income thresholds that generates income through fees generated through the provision of commercial equine activities including, but not limited to riding lessons, trail riding activities or training of horses and the production for sale of crops, livestock, and livestock products

- “Timber operation,” or the on-farm production, management, harvesting, processing, and marketing of timber grown on the premises into woodland products, including logs, lumber, posts and firewood conducted as part of an active farm operation, provided however that the annual gross sales value of such processed woodland products does not exceed the annual gross sales income from the production, preparation and marketing of crops, livestock and livestock products conducted on the premises

- “Compost, mulch or other organic biomass crops,” or the on-farm processing, mixing, handling, or marketing of organic matter grown or produced by such farm operation, or imported off-farm generated organic matter necessary to facilitate the composting of such farm operation’s agricultural waste, for the purpose of producing compost, mulch or other organic biomass crops that can be used as fertilizers, soil enhancers or supplements, or bedding materials

These activities, although some not traditional agriculture, nonetheless are protected activities within county agricultural districts, and need to be accommodated within local zoning codes. The best approach would be to define these activities clearly and concisely, as parts of a larger agricultural operation. In the case of commercial horse boarding and commercial equine operations, a combined definition would be appropriate. Also, since these two enterprises invite the public onto the premises, municipal site plan review and approval with basic site design standards is appropriate (see Site and Design Standards section).

For the purpose of the local zoning code, agriculture should be defined in a manner that is similar to the definition of farm operation in the Agriculture and Markets Law, Section 301. An example definition is:

“The use of land and on-farm buildings, equipment, manure processing and handling facilities, and practices which contribute to the production, preparation and marketing of crops, animal husbandry, livestock and livestock products as a commercial enterprise, including a commercial horse-boarding operation as defined in the Agriculture and Markets Law Article 25-AA, Section 301, and timber processing as defined in this zoning law.”

In addition to promoting more farm-friendly approaches to regulating land uses, the following sections also address the issue of conformance with the New York State Agriculture and Markets Law as it relates to local zoning.

Agriculture-Related Businesses

Agriculture-related businesses are small-scale businesses operated by a farmer as a supplemental source of income for the larger farm operation. They are businesses that do not fall under the Department of Agriculture and Markets “…the production, preparation and marketing of crops, livestock and livestock products…” palette of agricultural activities. Instead, they are businesses that directly or indirectly support agriculture by providing critical materials and services to the surrounding farm community. An example definition is[1]:

“A retail or wholesale enterprise operated as an accessory use to an active farm on the same premises, providing products or services principally utilized in agricultural production, including structures, agricultural equipment and agricultural equipment parts, batteries and tires, livestock, feed, seed, fertilizer and equipment repairs, or the sale of grain, fruit, produce, trees, shrubs, flowers or other products of agricultural operations, and including breweries, cideries, distilleries, wineries, and juice production that are not otherwise specifically defined as a farm operation.” -Town of Geneva Zoning Code, Section 165-3

A key component of this definition is the language “…operated as an accessory use to an active farm on the same premises…” This verbiage is very important, as it prevents the development of stand-alone business enterprises that would not otherwise be permitted in the zoning district. In some zoning regulations, there may be physical limits on the physical size of these businesses (not to exceed 2,500 sq. ft.) or limits on the number of employees as a means of controlling their size and scale. If these businesses have outside employees or generate traffic due to shipments of deliveries, or are open to the public, municipal site plan review and approval process with basic site design standards is appropriate (see Site and Design Standards section).

Agri-Tourism

Agri-tourism is seen as both a means for farmers to generate additional revenues outside their main agricultural operations, and as a local economic development tool that can draw tourism into the community. It can be seasonal, a year-round enterprise, or a single annual event. Agri-tourism can also vary in its scale and the number of people it can attract, from a bed-and-breakfast to an on-farm creamery with a few hundred or less visitors per day, to thousands for a large winery or an annual or seasonal event. As a result, agri-tourism operations need careful attention in terms of definition, as well as ensuring the health and safety of the general public, and in some cases ensuring that local roads and highways are adequate to accommodate traffic.

The Department of Agriculture and Markets definition of agri-tourism makes it clear that the agri-tourism enterprise must be directly tied to the sale, marketing, production, harvesting or use of the products of the farm, but also have some sort of educational component. This educational component can include a variety of activities, including formal tours, informational displays, educational demonstrations, farm animals petting and feeding activities, and signs and displays. An example definition is:

“An agriculture-related enterprise, operated as an accessory use to an active farm operation engaged in the production, preparation and marketing of crops, animal husbandry, livestock and livestock products as a commercial enterprise, which brings together tourism and agriculture for the education and enjoyment of the public, and which may include: hay rides, corn mazes, hay mazes, petting zoos (farm animals only), farm tours and agriculture themed festivals and other public or private events, and including as subsidiary activities the sale of gifts, clothing, beverage tastings, prepared foods, food and drink service, and other items that promote the sale of agricultural products.”

As with the Department of Agriculture and Markets definition, this example emphasizes the tie to an active farm operation, the objective of promoting the sale of products of the farm operation, and education to enhance the public’s awareness of farming and farm life. Since agri-tourism enterprises invite the general public onto the premises, municipal site plan review and approval with basic site design standards is appropriate (see Site and Design Standards section).

Farmstands and other Forms of Direct Farm Marketing

From the traditional seasonal farmstand, direct farm marketing has expanded to wide variety of activities, such as the year-round sale of fresh fruits and produce, meats, milk products, baked goods, and processed foods, to farmers’ markets, to community supported agriculture, to the online sale of processed and unprocessed agricultural products. The common attribute of the many types of direct farm marketing enterprises is that they bypass the traditional practice of the farmer selling their product through wholesale markets: the farmer instead sells directly to the retail consumer.

Historically the most recognized form of direct farm marketing has been the temporary or permanent farmstand, or the sale of greenhouse plants and horticultural products. Often though the definition of a farmstand restricted them to being a temporary structure, and restricted sales to seasonal produce grown on the premises. Although considered agricultural operations under state law, greenhouses are often limited to commercial zoning districts.

Communities should review their zoning codes to ensure that they reflect the contemporary nature of direct farm marketing, as well as Agriculture and Markets Law. Do zoning regulations unduly restrict farmers from engaging in direct farm marketing, for instance with restricting farmstands to temporary and seasonal operation only? Do the regulations permit the wider variety of direct farm marketing enterprises that farmers may engage in today? Are the definitions up to date, both in terms of permitting these enterprises, as well as adequately defining what constitutes a direct farm marketing enterprise?

An example definition for direct farm marketing is:

“A retail enterprise operated as an accessory use to an active farm operation on the same premises, that is engaged in the sale of grain, fruit, produce, trees, shrubs, flowers, meats, processed foods or other products of agricultural operations, or gifts, clothing, beverage tastings, prepared foods, food and drink service, and other items that promote the sale of agricultural products, and including breweries, cideries, distilleries, wineries, and juice production that are not otherwise specifically defined as a farm operation.”

This definition both broad enough, and yet limits such enterprises to being accessory uses to an active farm operation. It can be supplemented with more specific definitions for some activities, such as a farmstand:

“A permanent or temporary structure and accessory use to an ongoing agricultural operation, with or without appurtenant open display area, for the retail and wholesale sale of agricultural produce and other natural, processed or manufactured food products which are directly linked to and promote the use and sale of agricultural products.”

Other supplemental definitions that should be considered for specific types of direct farm marketing are definitions for on farm breweries, cideries, distilleries, and wineries.

Depending on their character, municipal site plan review and approval with basic site design standards is an appropriate zoning tool for some direct farm marketing enterprises. Small farmstands or small self-serve stores in existing structures that meet simple design standards such as adequate parking set back from the shoulder of streets and roads, limits on size, and signs, may be approved through a building permit review process. For larger direct marketing enterprises that invite the public onto the premises, municipal site plan review and approval with basic site design standards is appropriate (see Site and Design Standards section).

Commercial Food Processing

Small-scale on-farm commercial food processing, including baked goods, jams and jellies, pickles, and canning, can be another source of supplemental revenue for an agricultural operation. These businesses can also help fill a major gap in the local and regional food systems and promote “buy local” economic development. Commercial food processing operations however need to be listed as an accessory use to an ongoing agricultural operation and defined in a manner that ensures they are a subordinate activity to the operation. It is appropriate to include in the zoning code limits on square footage, or the number of non-resident employees working at the business as a means of maintaining the small scale “cottage” character of the business. An example definition for on-farm food processing is:

“The production or processing of whole fruit and vegetables, baked cakes, muffins, pies or cookies, candy, jellies, jams, preserves, marmalades, and fruit butters, cheeses, butters, and other milk derived products, meats and meat products and other foodstuffs, as regulated by state and federal law, for wholesale or retail sale, and operated as an accessory use to an active farm operation engaged in the production, preparation and marketing of crops, animal husbandry, livestock and livestock products as a commercial enterprise.”

Note that this definition does not limit the on-farm food processing enterprise to using fruits, vegetables, milk or other products of the active farm operation. As with the case of farm breweries, cideries, distilleries and wineries, a host farm likely does not produce all the ingredients utilized in the food processing operation, especially in the case of seasonal fruits and vegetables, or for a bakery operation. The primary objective of permitting such businesses in zoning however is not necessarily to provide outlets for the production of the farm, but rather provided a supplemental revenue stream for the larger agricultural operation.

Site plan approval is appropriate for such uses. Although they usually ship their product in small lots, these small commercial kitchens do generate some van or truck traffic, especially if they engage in internet-based marketing that requires daily pick-up of merchandise. Some also conduct direct sales to the general public, which justify site plan review as a means of protecting the health and safety of the general public (See Site and Design Standards section).

Farm Breweries, Cideries, distilleries, wineries

Small-scale on-farm breweries, cideries, distilleries and wineries can be another source of supplemental revenue for an agricultural operation. These businesses can also help fill a major gap in the local and regional food systems and promote “buy local” economic development. These operations however need to be listed as an accessory use to an ongoing agricultural operation and defined in a manner that ensures they are a subordinate activity to the operation.

Example definitions for on-farm breweries, cideries, distilleries and wineries are:

On-farm brewery:

An enterprise engaged in the production for sale of beer, operated as an accessory use to an active farm operation on the same premises, licensed and regulated as such by the State of New York, and including as subsidiary activities the sale of gifts, clothing, beverage tastings, prepared foods, food and drink service, and other items that promote the sale of agricultural products.

On-farm cidery:

An enterprise engaged in the production for sale of cider, operated as an accessory use to an active farm operation on the same premises, licensed and regulated as such by the State of New York, and including as subsidiary activities the sale of gifts, clothing, beverage tastings, prepared foods, food and drink service, and other items that promote the sale of agricultural products.

On-farm distillery:

An enterprise engaged in the production for sale of liquor is manufactured primarily from farm and food products, operated as an accessory use to an active farm operation on the same premises, licensed and regulated as such by the State of New York, and including as subsidiary activities the sale of gifts, clothing, beverage tastings, prepared foods, food and drink service, and other items that promote the sale of agricultural products.

On-farm winery:

An enterprise engaged in the production for sale of wine, brandies distilled as the by-product of wine or other fruits, or fruit juice, operated as an accessory use to an active farm operation on the same premises, licensed and regulated as such by the State of New York, and including as subsidiary activities the sale of gifts, clothing, beverage tastings, prepared foods, food and drink service, and other items that promote the sale of agricultural products.

Site plan approval is appropriate for such uses. Some also conduct direct sales to the general public, which justify site plan review as a means of protecting the health and safety of the general public.

Since these types of farm enterprises invite the general public onto the premises and can also generate increased traffic to and from the location, municipal site plan review and approval with basic site design standards is appropriate (see Site and Design Standards section).

Farm Worker Housing

Farm worker housing, both seasonal and year-round housing for farm laborers, and is included in the term “on-farm buildings” in the definition of farm operations in the Agriculture and Markets Law, Sect. 301. For some farm operations, farm worker housing is a necessary accommodation for their workers due to the long workdays, sometimes 24-hour operations of farms, and the often on-call nature of the profession. Farmworker housing can also address the shortage of nearby affordable rental housing in many rural areas. The use of manufactured homes (a.k.a. mobile homes) as farm worker housing is a common practice, as is the placement of the housing on the same parcel of land as other farm buildings. Local zoning may not require farmworker housing to be sited on a separate or subdivided parcel, so long as minimum zoning setbacks from property lot lines, any required setbacks between buildings, and public health laws requirements for adequate water and sewage disposal facilities are met.

Towns with agricultural operations that may require farmworker housing should provide for it in their zoning regulations. It should be listed as an accessory use to an active farm operation and clearly defined in the definitions section of the regulations. In the interest of clarity, the definition of farmworker housing should include manufactured homes, modular homes, and stick-built homes as an option. An example definition for farm worker housing is:

“A dwelling or dormitory unit located on an active farm operation that is accessory to such operation which may be occupied by employees of the farm and their families, or unrelated employees of the farm, which may consist of manufactured homes, modular homes, and which may be located on the same parcel.”

Towns may impose reasonable conditions such as occupancy by farm employees and their families, and parking provisions. Elevated levels of review, such as site plan approval or special use permit approval, that are not required for similar types of dwellings may be consider an unduly burdensome regulation of a farm operation and should be avoided.

Home Occupations

Working from the home has been a feature of American culture from colonial times, and “home occupation” is a standard in the list of permitted accessory uses in zoning regulations in the United States. Generally, a home occupation is the use of space in a personal residence for a professional or service type business or employment activity that is secondary to the residential use of the structure and does not affect the residential character of the home. A home occupation generally does not include non-resident employees and does not attract walk-in or drive-in clients or customers. An example definition for home occupations is:

“A business conducted within a dwelling, or a building accessory thereto, by a resident of the dwelling, which is clearly incidental and secondary to the use of the property for residential purposes, and which is the type of business that is customarily conducted within a dwelling or building accessory thereto.” – Town of Ithaca Zoning Code

Home businesses are like home occupations but more flexible. As with home occupations, these are permitted accessory uses to the primary residential use of the dwelling or residential property and operated by a resident of the premises. They differ from home occupations in that a limited number of employees may also be permitted (three is a common number), and they attract a limited amount of walk-in or drive-in traffic to the site.

In urban and suburban areas examples of such home-based businesses or professional offices are architects, attorneys, dentists, doctors, engineers, and financial consultants. More importantly, from the standpoint of agriculture, they include veterinary offices and service businesses that specialize in agriculture and need to be accessible to their client base.

“An office of an accountant, business consultant, financial consultant, attorney, architect, engineer or other design professional, forester, medical or dental professional, veterinarian or other related occupations located within their residence or an accessory building, where activities are limited to providing services not involving direct sale of goods, as an accessory use to a dwelling or farm operation, and not occupying more than 600 sq. feet of gross floor area, and not employing more than 3 employees not living on the premises.”

Due to their small scale and other characteristics, home occupations can be listed as a permitted accessory use, without site plan approval or special approval requirements. Site plan approval however is an appropriate level of review for home-based businesses or professional offices, to ensure the health and safety of employees and customers of the business, and compliance with zoning and site design standards.

Signs for Agriculture and Rural Businesses

Most local governments have regulations governing signs in a separate sign law or as a regulation nested within their zoning code. However, farms and many rural businesses are often located off main highways and lack the exposure businesses located on main highways enjoy. Moreover, they can be difficult to find by first-time customers as well as out-of-town visitors and tourists. The business directional sign concept allows such agriculture related and other rural businesses to erect signs off their property for the purpose of directing prospective customers to their location. Business directional signs may be placed at intersections, upon receipt of a permit from the local government and the permission of the host landowner. An example definition for business direction signs is:

“A sign located off the premises on which a business is located, not exceeding nine square feet in area, posted by the business along a public road or highway for the purpose of guiding prospective customers to their location.” – Town of Geneva Zoning Code

Some basic standards for business directional signs are:

- In any zoning district where business directional signs are allowed, there shall be allowed no more than two such signs within the Town for any one business

- No business directional sign shall exceed nine square feet in area, nor exceed five feet in height at the top of the sign

- No business directional sign shall be placed more than 500 feet from the intersection at which prospective customers are being directed to turn off the road or highway along which said sign is located

- No business directional sign shall be located more than two miles from the business that it advertises

Lot Requirements/Density Controls/Setbacks

Controlling density has been a key objective of zoning regulations since their establishment, and the primary tool for achieving this has been setting minimum requirements for lot sizes, and minimum setbacks between structures and property lines, including public road rights of way. In rural areas without public water and sewer infrastructure, minimum lot sizes and setbacks also serve to protect the public health.

In most cases, the standard lot size and setback requirement in zoning regulations are not a major issue for agricultural operations, especially when they are applied uniformly to all uses in a zoning district. Problems can arise however when agricultural operations are treated differently, and subject to different, often larger setback requirements or lot size requirements. These additional requirements imposed on agricultural operations can have significant negative impacts on efficiency and economic viability of a farm. Examples include setbacks of sometimes 200 to 300 feet or more for barn structures and manure handling facilities. In an extreme case, a requirement for a 200-ft. setback from the property line of any “…manure, dust- or odor-producing substance…” has effectively rendered a longstanding farm operation illegal in one community.

It is important for communities to review the dimensional requirements in the zoning regulations to ensure that they are both reasonable, and do not unfairly target their agricultural operations or place unreasonable burdens on their ability to maintain their economic viability.

Renewable Energy

The movement toward renewable energy in New York today is presenting both opportunities, but also challenges, for municipal governments and farmers. Investment in smaller scale, non-commercial solar and wind energy systems to produce electricity to support their operations can reduce energy costs for farmers, while reducing reliance on fossil fuel energy sources. Large scale solar and wind energy developments, often referred to as commercial solar and wind energy, and which produce renewable energy for sale to the electric power grid, however, can have major implications in terms of agricultural land resources, and impacts to host communities. More information on solar energy development and agricultural lands is available at Onondaga County’s website regarding best practices for agriculture and solar and resources to help regulated and review solar energy systems (SOCPA Best Management Practices for Agriculture-Friendly Projects, 2021; SOCPA Solar 101, 2021).

Non-Commercial on-farm Renewable Energy Systems

Non-commercial renewable energy systems, whether solar or wind, are appropriate accessory uses to agricultural operations and should be permitted as such in zoning codes. Certain guidelines for governing the siting of solar arrays are appropriate, including:

- All solar arrays should meet all applicable setback requirements of the zoning district in which they are located, and should be located within the side or rear yard of the property

- The height of any solar array and its mounts should not exceed 15 feet or the height restrictions for accessory uses, whichever is greater, of the zoning district in which it is located

- The total rated output of the solar arrays at time of installation should not exceed 110% of the estimated maximum energy demand of the property[2]

- The total surface area of solar arrays, combined with all other buildings and structures on the lot, should not exceed fifty percent of total lot area

- Solar arrays should be located or adequately screened in order to prevent reflective glare toward any roads or highways or inhabited buildings on adjacent properties

- Solar arrays should be located on less productive lands such as inactive farmland, unimproved pasture or other lands, and avoid prime- or farmland of statewide importance

- If possible solar arrays and support structures, including structures for overhead collection lines, should be located at the edge of fields, and avoid or minimize disruptions to farm drainage and erosion control systems

- Access roads should be designed so that they are the minimum required width and built flush with the land surface to permit easy crossing by farm equipment

An example definition for a non-commercial solar energy system is:

“A solar photovoltaic cell, panel, or array, or solar hot air or water collector device, which relies upon solar radiation as an energy source for collection, inversion, storage, and distribution of solar energy for electricity generation or transfer of stored heat, primarily for use on the premises.” Town of Geneva Zoning Code

An example definition for non-commercial wind energy system is:

“An electric generating facility, whose main purpose is to convert wind energy to electrical energy, consisting of a wind turbine, a tower or other support structure and associated control or conversion electronics, which has a rated capacity of not more than 250 kW and which is intended to primarily reduce on-site consumption of utility power.” Town of Geneva Zoning Code

Although the footprint of on-farm wind energy systems and hence their impacts on land resources is much smaller than solar, consideration needs to be given to potential issues such as height, and tower failure and collapse. Some standards for siting non-commercial on-farm wind energy systems include:

- Limits on tower height, generally 80 ft. for lots smaller than 1 acre, and 200 feet for larger parcels

- Minimum setbacks from structures and property boundaries, including guy-wire anchors, of 1.5 times the tower height

- No wind energy system shall generate noise more than 50 dBA as measured at the closest property boundary, except during short-term events such as utility outages and/or severe windstorms

- The components of the wind energy system, including turbine blades, shall be coated with neutral colors and non-reflective finishes to minimize potential adverse visual impacts due to reflection and glare

- No exterior lighting shall be permitted on the structure above a height of 20 feet except that which is specifically required by the Federal Aviation Administration

While there is some concern regarding potential visual impacts of small wind turbines associated with their height, they are relatively small objects within the landscape and their visual impact is often reduced by woodland, hedgerows, and roadside vegetation. The following photo shows a small wind turbine located off Canty Hill Road in the Town of Otisco, viewed from a point on Otisco Road approximately 3,800 ft./.75 mi. away.

Small wind turbine located off Canty Hill Road, Town of Otisco, from approximately 3,800 ft./.75 mi. away.

Commercial Renewable Energy Systems

Commercial solar developments in New York have the potential to occupy hundreds of acres of land. They differ from on-farm non-commercial solar projects, as they sell their output directly to the energy grid for offsite consumption, as well as their much larger scale and land coverage. Commercial solar development however also offers farmers and farmland owners an attractive revenue source and can enhance the economic viability of farms. The challenge for farmland owners and local governments is that most attractive sites for commercial solar development however are relatively flat sites clear of trees and brush, that often are also covered by high quality agricultural soils. Although originally thought of as a minimal impact temporary use of land, the concrete and steel foundation systems for solar arrays are difficult to remove upon decommissioning. This may result in the permanent loss of high-quality agricultural lands.

Communities should accommodate commercial renewable energy development in their zoning regulations, but with appropriate siting and design controls in place. These can include:

- Construction on farmland designated as prime or farmland of statewide importance should be avoided

- Avoid active farm fields and improved pasture lands wherever possible, utilizing instead un-utilized land

- Avoid floodplains and wetlands, and disturbance of farm field tile and other drainage infrastructure

- To the extent practicable locate solar arrays along the periphery of fields and avoid segmentation of agricultural land

- The maximum height for freestanding solar panels located on the ground or attached to a framework located on the ground should not exceed 15 feet in height above the ground

- The total surface area of solar collectors, combined with all other buildings and structures on the lot, should not exceed fifty percent of total parcel area

- All solar collectors should be located in order to prevent reflective glare toward any roads or highways or inhabited buildings on adjacent properties

- All solar collectors should meet all applicable setback requirements of the zoning district in which they are located, but shall not be installed within 25 feet of any property line

- A landscaped buffer should be provided around all equipment and solar collectors to provide screening from adjacent residential properties and roads

- Removal of trees over 6 inches in trunk diameter should be minimized, or mitigated by replacement tree plantings elsewhere on the property

- Roadways to and within the site should be constructed of gravel or other permeable surfacing and shall be flush with the surrounding land contours

- All on-site utility and transmission lines should, to the extent feasible, be placed underground

- A decommissioning plan with financial surety for the development should be prepared for review and approval as part of the local approval process

Wherever possible, the co-location of solar arrays with compatible land use or agricultural activities such as pollinator habitat creation, animal grazing (sheep, goats, etc.), and the growing of shade tolerant crops such as certain vegetables, should be encouraged. Commercial solar development should be subject to at least site plan approval. Given the potential impacts on land resources, and community aesthetics, a special permit review process may also be appropriate.

An example definition for a commercial solar energy system is:

“An area of land or other area used for a solar collection system principally used to capture solar energy and convert it to electrical energy to transfer to the public electric grid in order to sell electricity to or receive a credit from a public utility entity, but also may be for on-site use, and which may consist of one or more freestanding ground- or roof-mounted solar collector devices, solar-related equipment and other accessory structures and buildings, including light reflectors, concentrators, and heat exchangers, substations, electrical infrastructure, transmission lines and other appurtenant structures and facilities.” – Town of Geneva Zoning Code

Large scale commercial wind energy development has potentially large impacts on community character and requires special consideration in the context of zoning. Its potential impacts on agricultural lands or agricultural operations are significantly less than commercial solar development, however, for agricultural areas there are some recommended standards that should be adopted by local governments. These include:

- Minimize impacts to normal farming operations by locating structures along field edges and in nonagricultural areas, where possible

- Avoid dividing larger fields into smaller fields, which are more difficult to farm, by locating access roads along the edge of agricultural fields and in nonagricultural areas where possible

- All existing drainage and erosion control structures such as diversions, ditches and tile lines shall be avoided or appropriate measures taken to maintain the design and effectiveness of the existing structures, and any structures that are disturbed or destroyed shall be restored

- The surface of access roads constructed through agricultural fields shall be level with the adjacent field surface

- Where necessary, culverts and water bars shall be installed to maintain natural drainage patterns

- All topsoil shall be stripped from agricultural areas prior to construction and stockpiled separate from other excavated material such as rock and subsoil, and immediately adjacent to the area where stripped/removed, and shall be used for restoration of that particular area

- All areas impacted by construction or heavy vehicle traffic shall be de-rocked and de-compacted upon completion of the project

- In cropland, hay land and improved pasture, a minimum depth of 48 inches of cover will be required for all buried electric cables, and in other areas, a minimum depth of 36 inches of cover will be required

- Unless on-site disposal is approved by the landowner, all excess subsoil and rock shall be removed from the site

- Excess concrete will not be buried or left on the surface in any active agricultural areas of the site

An example definition for a commercial wind energy system is:

“An electric generating facility, whose main purpose is to convert wind energy to electrical energy to transfer to the public electric grid in order to sell electricity to or receive a credit from a public utility entity, but also may be for on-site use, consisting of one or more wind turbines and other accessory structures and buildings, including substations, meteorological towers, electrical infrastructure, transmission lines and other appurtenant structures and facilities.” -Town of Geneva Zoning Code

NYS Section 94-c Review of Very Large Renewable Energy Developments

The Accelerated Renewable Energy Growth and Community Benefit Act created an Office of Renewable Energy Siting (ORES) to oversee the approval of commercial solar and wind energy developments that will generate 25 MW or more of power per year. This process effectively pre-empts local regulations and review of such projects.

However, Section 900-2.25 of Title 19 of NYCRR Part 900, which governs the ORES review process does require that the location of a proposed renewable energy development conform to all substantive requirements of “local ordinances, laws, resolutions, regulations, [and] standards,” including local zoning. The applicant must also state whether the municipality has adopted a comprehensive plan, and whether the proposed renewable energy development if consistent with the adopted plan.

Under NYS Executive Law Section 94-c, the Office of Renewable Energy Siting may elect to apply, or not apply applicable local zoning and other regulations to the proposed development. To override local regulations, the Office must make a finding that the local regulation is “unreasonably burdensome” in view of the renewable energy development and greenhouse gas emission reduction targets set forth in Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA) and the environmental benefits of the proposed facility.

This new State role in the review and approval of large commercial renewable energy projects highlights the need for local government to be proactive. Towns, villages and cities should have in place an adopted comprehensive plan or farmland protection plan that clearly communicates their policy with regard to the protection of their best quality agricultural soils, and a clear rationale for doing so. Local land use regulations also must be clear in terms of which zoning districts such development is permitted, and also have clear design and operating standards for such development, including prohibitions on developing on prime farmland and farmland of statewide importance.

Although local government does not have a direct role in the ORES review process, it can effectively position itself to influence the State’s deliberation through its zoning and other regulations.

Subdivision & Other Land Use Regulations

Subdivision of Agricultural Lands

Land subdivisions to create a new building lot, or multiple building lots, can have unintended consequences for agricultural operations if not done in a thoughtful manner. With the size of modern farm equipment, even a poorly subdivided single lot located in the middle of a large field, can disrupt and slow down everything from plowing/tilling to planting to harvesting. Field drainage infrastructure can inadvertently be damaged or destroyed, causing wet soil conditions and lowered productivity. Residential wells drilled too close to a building lot boundary may be susceptible to contamination from manure spreading. In some communities, bans on spreading manure within 100 or 200 feet of residential wells have been suggested, creating restrictions that could force farmers to take land out of production.

There are several steps that local governments can take to minimize the adverse impacts of subdivisions in agricultural areas. Some consist of amendments to into the zoning code, while others include amendments to the subdivision regulations. In terms of zoning, a good first step is for local governments to review minimum lot size and width requirements. It may be counterintuitive, but permitting smaller lots in agricultural areas, especially in low growth agricultural areas, can preserve agricultural lands better than larger lots. Larger 5- to 10-acre lots are often intended to protect rural character by spreading out the homes and creating large gaps between them. In agricultural areas, however, they result in wasted land – too small to farm and too large to mow. A smaller wider lot configuration, for example a 1.5-acre lot coupled with a minimum lot width requirement of 220 feet in contrast can accommodate a home while also permitting 100-ft. setbacks between a water well, the lot boundaries, and an onsite septic system. This wider lot configuration can reduce the potential for well contamination and provide additional buffer areas between the new home and farm operations on adjacent fields. It also reduces the impact on the agricultural land resources, reserving 3.5- to 8.5-acres for continued agricultural use compared to very large lot zoning. Two-acre or 2.5-acre residential lots, while consuming more land, nonetheless have less impact on the agricultural land resource than very large lot zoning.

Fixed-Ratio (Density-Averaging) Zoning

The common method of imposing very large lot dimensional requirements, such as 5-acre or 10-acre or larger minimum lot sizes, does not work well to protect agricultural lands. While large lot zoning can reduce the development potential of rural areas, it can lead to the fragmentation of agricultural lands by locking up land in excessively large residential lots (“too small to farm, too large to mow”). The fixed-ratio zoning and subdivision concept was developed in agricultural counties in southern Pennsylvania in the 1970s as a way of providing farmers with the option of occasional sales of land, usually for a house lot, without triggering large scale development or farmland fragmentation. It reduces the density of development in an area without locking up productive farmland in non-farm residential lots. Also known as “density averaging,” the fixed-ratio zoning and subdivision combination can be very effective also in protecting ecologically important and scenic lands.

Fixed-ratio zoning differs from the conventional approach of controlling the minimum size of individual lots. It instead controls the number of lots permitted to be subdivided off a parent tract of land. It also differs in that it sets a maximum permitted lot size for non-agricultural or non-open space uses, as the means to control fragmentation of lands. This “one lot per X acres” approach, – e.g., 5 acres… 10 acres… 20 acres of land – has been proven to be an effective way to control density in rural areas and prevent land fragmentation.

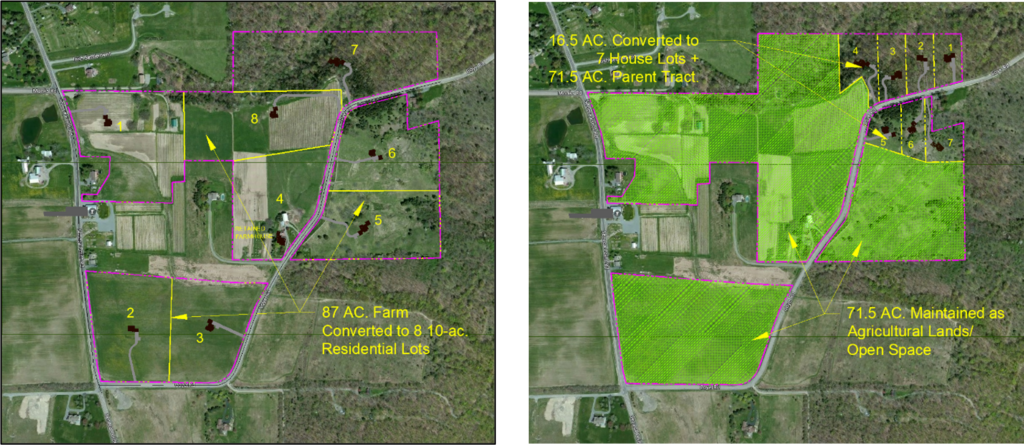

In the following graphic, the conventional subdivision scenario with a 10-acre minimum lot size, would net the sub-divider 8 lots on the 87-acre farm tract. With density set at one lot for each 10 acres of land in the same hypothetical parent tract of 87 acres, up to seven 2-acre lots would be permitted to be subdivided off the parent tract. In this scenario these lots together consume only 16.5 acres of the 87 acres, leaving 71.5 acres in one large tract that can continue in agricultural use. The 7 building lots are also located on the lower quality soils such as pastureland and woodland.

Comparison of large-lot zoning with 8 development lots meeting the conventional minimum 10-acre lot size requirement (left), and a subdivision utilizing the fixed-ratio zoning concept. Note that the parcel in the middle is left out because it is a separate property. Under the fixed –ration approach, the same number of lots is permitted (8), but the 7 lots allocated for residential development are only about 2-acres in size, while 71.5 acres are retained for agricultural use. Fixed-ration zoning can thus conserve agricultural land resources. while still permitting landowners the option of small-scale development.

This fixed-ratio approach can work well because most farmers and other rural landowners are generally not interested in seeing their land developed, but instead need the ability to sell off an occasional lot, as needed or desired. The fixed-ratio approach can satisfy this desire, over a period of years, while maintaining contiguous tracts of productive farmland and other open space. Coupling fixed-ratio density controls and lot size limits with other tools such as flag lots can permit greater flexibility protecting prime agricultural lands.

Because fixed-ratio zoning is designed for use in rural zoning districts with low numbers of subdivisions and involving the creation of a few lots, the tracking of land subdivision is relatively simple. Upon adoption of the new fixed-ration zoning, the size of all affected parcels, along with the number of lots permitted to be created under the new zoning are recorded. As subdivisions occur, they are duly recorded and tracked in this database, until the maximum number of created lots is reached. With GIS technology, this record system can easily be set up and maintained.

Flag Lots

A secondary option is to amend the zoning regulations to permit “panhandle” or “flag” lot configurations. These lots are characterized by long narrow strips of land connecting the road frontage with a lot set back from the roads. The long narrow strip – the “handle” or “flagpole” should be wide enough for a driveway plus buffers on either side (30 feet width = 12-ft wide driveway + 9-ft wide buffers). The portion of the lot where the house would be built must meet the minimum area requirements and lot width and depth requirements outlined in the zoning regulations. This excludes the area occupied by the handle or flagpole portion of the proposed lot.

A legitimate concern regarding the flag lot approach to subdivision is access for emergency vehicles. To permit adequate, year-round access for emergency vehicles, especially heavy firetrucks, the driveway servicing a flag lot, including any culverts, must be designed built to support heavy trucks. This can be address through design standards that require the use of compacted crushed stone to ensure an all-weather surface, even in spring thaw conditions.

In addition to a minimum width of 30 feet for the access strip to the public road or highway, other recommended design standards for flag lots are:

- The driveway shall be a minimum of 12 feet wide shoulder to shoulder, with a maximum gradient of 10%

- The driveway shall be of all-weather construction, with a sub-base consisting of at least twelve (12) inches of compacted crushed limestone or crushed bank-run gravel, with adequate coverage over any culverts

- The minimum radius of any curve in the driveway shall be 50 feet measured from the centerline

- A horizontal clear area measuring at least 10 feet from the centerline of the driveway on both sides, and a vertical clear area of at least 15 feet from the surface of the driveway to the lowest tree branches, shall be created and maintained

- There shall be adequate sight distance in both directions where the driveway intersects with the public road or highway

- Whenever practicable, adjoining flag lots should be platted in a manner that encourages shared driveway access points along public roads and highways

Farm Master Plan

The fact that many subdivisions in rural agricultural areas are occasional subdivisions to create a single lot – often for a family member – contribute to the fragmentation of farmland, impacts on environmentally sensitive areas, and on rural character. Farmers and farmland owners can avoid them, by taking a “big picture” look at their land holdings, and develop a long-term plan regarding where, and when, they might subdivide off lots in the future. It does not have to be a formal, detailed plan, but a vision for what the farm could be in 20 or 30 years in the future. By having a vision for the future, farmland owners can then develop a long-term strategy for subdividing their land. They can then assess the potential benefits and drawbacks of creating development lots in specific locations on the farm and avoid problems down the road. With a vision in place, the steps in creating a simple strategy for subdividing land are:

- Determine the desired number of lots to be created (i.e. the desirable number of non-farm neighbors)

- Consult local zoning and subdivision regulations, code enforcement officials, and health department regulations to determine minimum lot size requirements, including minimum requirements for frontage on public roads, and setback requirements for water wells and septic systems

- Review survey and other mapping for the farm and identify local roads and the length of available road frontage

- Identify areas on the farm that are woodland or brush and meadow, or pastureland (often indicators of poorer soils)

- Identify hedgerows, drainageways and other field boundaries

- Consult with County or local planning departments for information on floodplains, wetlands, and other environmentally sensitive areas of the farm

- Check the soils mapping for the farm, to identify the areas of high-quality soils, and the areas of lower quality soils

With this information in hand the farmland owner can locate sites for future lots based on access from public roads and highways and utilize less productive land for development while protecting the highest quality farmland. They can also limit fragmentation of farm fields by shifting new lots toward hedgerows, property lines, drainageways and other edge locations on their property. With the use of flag lots (if permitted by zoning), the landowner can locate new building lots to woodland areas to rear of productive farm fields that front on public roads and highways, or stack lots behind each other, further minimizing the fragmentation of fields.

Many municipal governments include in their subdivision approval processes a preliminary sketch plan review. Sketch plan review is an informal, advisory review of a proposed subdivision. Although no approval is involved, it can be an opportunity for the landowner to discuss their plan with the Planning Board and get feedback on it. This simple farm master planning exercise can provide the landowner the option of subdividing lots over a period of years, while that also maximizing protection of the agricultural land resources, and economic viability of the farm.

Conservation Subdivision

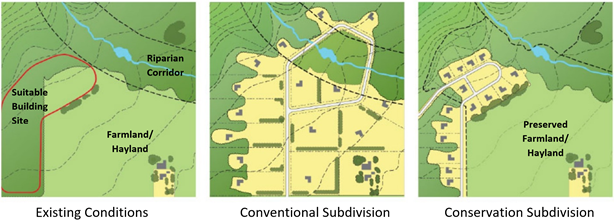

Local governments should also review their subdivision regulations, and amend if appropriate to permit the use of conservation subdivision design in agricultural areas. Historically, cluster subdivision design, as permitted under Section 278 of Town Law, has been associated with attached housing (townhouse developments in built-up suburban areas). The conservation subdivision concept is a variation of the cluster subdivision concept that has become a useful growth management tool in rural areas where development often takes the form of smaller scale single-family residential development.

A conservation subdivision utilizes the careful placement of individual homes on a site in a manner that avoids productive agricultural lands and environmentally sensitive areas. Due to the lack of public water and sewer, lot sizes are larger (e.g. 1 acre or larger or 210 ft. x 210 ft.) than typical suburban cluster subdivisions on smaller lots. In an agricultural zoning district with minimum lot sizes of 2 acres or 2.5 acres, the conservation subdivision can nonetheless can be an effective tool for protecting agricultural lands, environmentally sensitive areas, and rural character. Through more flexible lot dimensional standards, as well as street design provisions that permit narrower, low speed and low-volume private lanes to access multiple homes, conservation subdivisions can provide development opportunities for farmers and other owners of large tracts of land, while preserving rural character and the agricultural land base.

In addition, the subdivision regulations should be amended if necessary to require that applications for subdivision include on the proposed subdivision plat any existing drain tile system or other field drainage infrastructure. Any subdivision approval should have as a condition that the subdivision applicant make provisions for preserving such infrastructure, or replacing it where necessary. Such action will prevent field drainage problems upstream and downstream of the subdivision.

Illustration of the conservation subdivision design approach, from the Dutchess County Greenway .

Site Plan Review

The purpose of the Site Plan Review Process is to review plans for specific types of development to ensure compliance with all appropriate land development regulations, compliance with accepted design principles for traffic access and circulation, parking, pedestrian facilities, stormwater management facilities and other design details, and consistency with adopted municipal plans. Generally, in zoning codes site plan review is required for developments where the general public has access to, such as multi-family housing, commercial and industrial development and non-government institutions such as hospitals, private schools, and religious uses. The three primary objectives of site plan review are: 1) to ensure conformance with relevant land use regulations; 2) to ensure the design of the development protects the health and safety of the public that enters the site; and 3) ensure (through SEQR review) that potential adverse environmental impacts are identified and mitigated to the extent practicable.